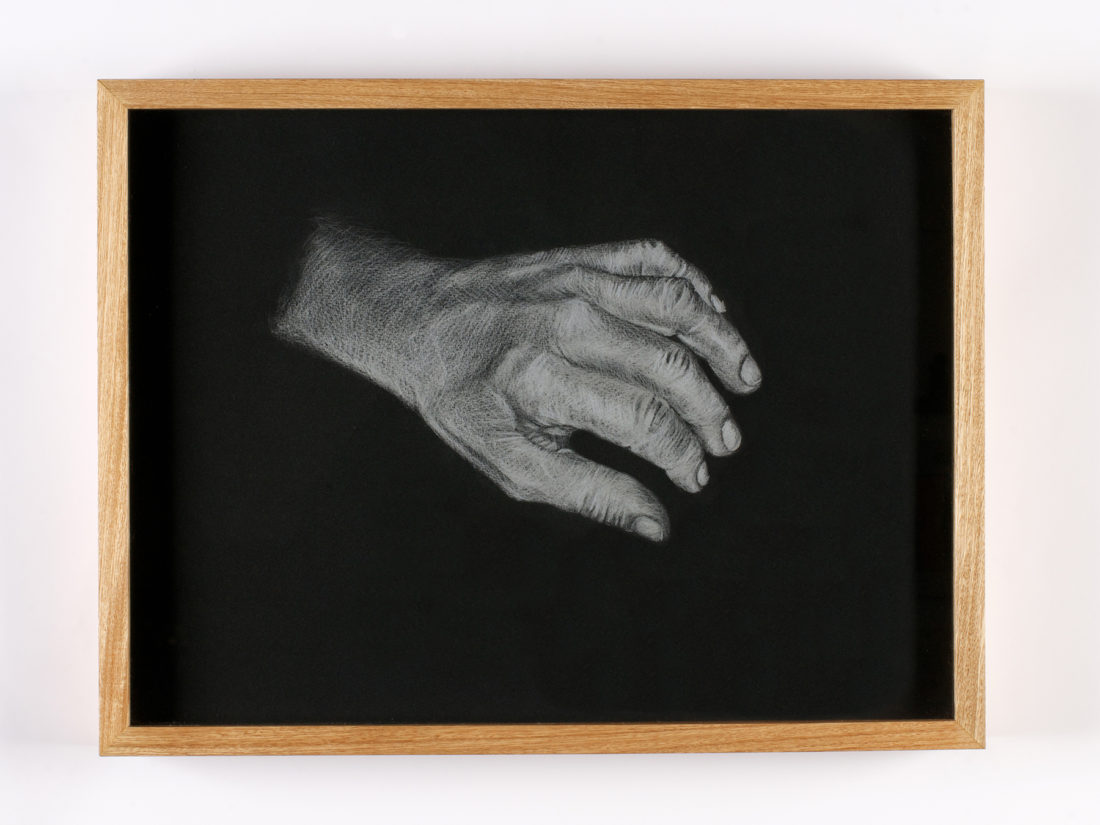

Mano izquierda

To Grasp, But Not Possess: Isa Carrillo’s Left Hand

Mary K. Coffey

“Ideas are to objects as constellations are to stars.” (1)

“We are stardust

Billion year old carbon

We are golden

Caught in the devil’s bargain

And we’ve got to get ourselves

Back to the garden.” (2)

In Isa Carrillo’s Rising Constellation we face three identical images of the night sky. In one, we see a painted field of stars. In the next, some of these stars are conjoined in a constellation in the form of an outlined hand. In the final image, the constellation has been enhanced with contour lines that give it an illusory sense of dimension. Despite the effects of drawn illusion, its ephemeral presence threatens at any moment to dissolve back into a field of disparate points of light. In this series of drawings Carrillo presents us with the “ghost” of Orozco’s left hand, an appendage that was blown up in an accident with explosives when the artist was a young man.

Orozco’s accident definitively put an end to his family’s aspirations for him to become an engineer, allowing him to pursue painting professionally, while also leaving him physically deformed. This accident was, therefore, both fortuitous and traumatic, encouraging some to see Orozco’s career-long interest in the generative and destructive power of fire as biographical in origin(3). In his Prometheus mural, for example, we see the Titan striving toward what is presumably the flame he stole from the gods. This theft comprises his gift to mankind, a liberating act for which he was brutally punished. Formally, Prometheus’ hands seem to disintegrate in the blaze, suggesting that there is a great price to be paid for the audacity of god-like ambition. If, in fact, Prometheus is an allegory of the modern artist, then Orozco presents us with a series of tensions, between creativity and destruction, between liberation and bondage, between earth-bound matter and the immateriality of the divine.

Carrillo too presents us with a series of unresolved tensions. Her idiom is more conceptual and relational than Orozco’s expressionist bombast. She graduated from the University of Guadalajara with a degree in Visual Arts in 2005. Like Orozco, her practice is deeply engaged with mysticism. But in her case, she has dedicated six years to the study of chirology, the ancient practice of reading hands, popularly understood as “palm reading,” a form of fortune telling. In her installation, Left Hand, first exhibited at the Casa Taller José Clemente Orozco in 2015 and from which this selection of objects derives, she used chirology to analyze photographs of Orozco’s existing hand in an attempt to glimpse the artist’s personality.

Carrillo’s recourse to esoteric diving practices—such as chirology, astrology, and graphology—calls into question the legacy of the Enlightenment. Like Orozco, she employs an aesthetic of the fragment to activate her project. For Orozco this legacy inheres in the idealizing form of the academic nude. For Carrillo, it is vested in the disenchanted world of scientific reason and its techniques of reproduction. In Orozco’s Prometheus the locus of these tensions is the torqued body of the Titan. In Carrillo’s installation it is the constellation. Rising Constellation might be read, therefore, as an allegorical image that encourages contemplation of the fragment’s relation to the whole, the individual’s connection to the universe, the relationship between esoteric knowledge and science, and the materialization of the immaterial. As she describes it in her fable-like account of the hand’s life, upon its liberation from the artist’s body, Orozco’s left hand rematerialized in outer space as a constellation.

German philosopher Walter Benjamin seized upon the constellation as a key metaphor in his attempts to theorize the role of allegory in a fallen world as well as the power of constructivist montage to create new material arrangements out of the fragments that result from the destruction of the bourgeois scheinwelt (world of illusions). Arguing that, “ideas are to objects as constellations are to stars,” Benjamin suggested that the montaged fragments of the destroyed scheinwelt disclose an idea that is at once comprised of these disparate parts while also pointing to a “higher unity that is implicit within them but cannot be ‘grasped’ or possessed as an object itself.”(4) In this sense the constellation conjures a figure without reconstituting the illusion of presence, completeness, or an illusory whole.

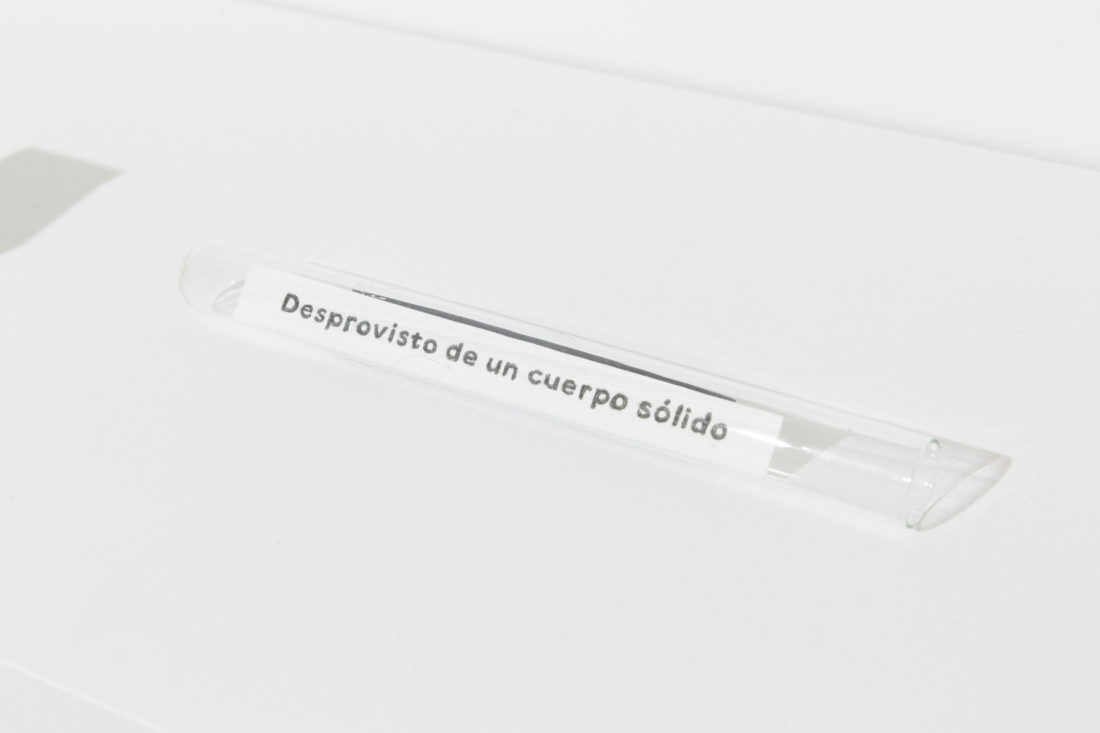

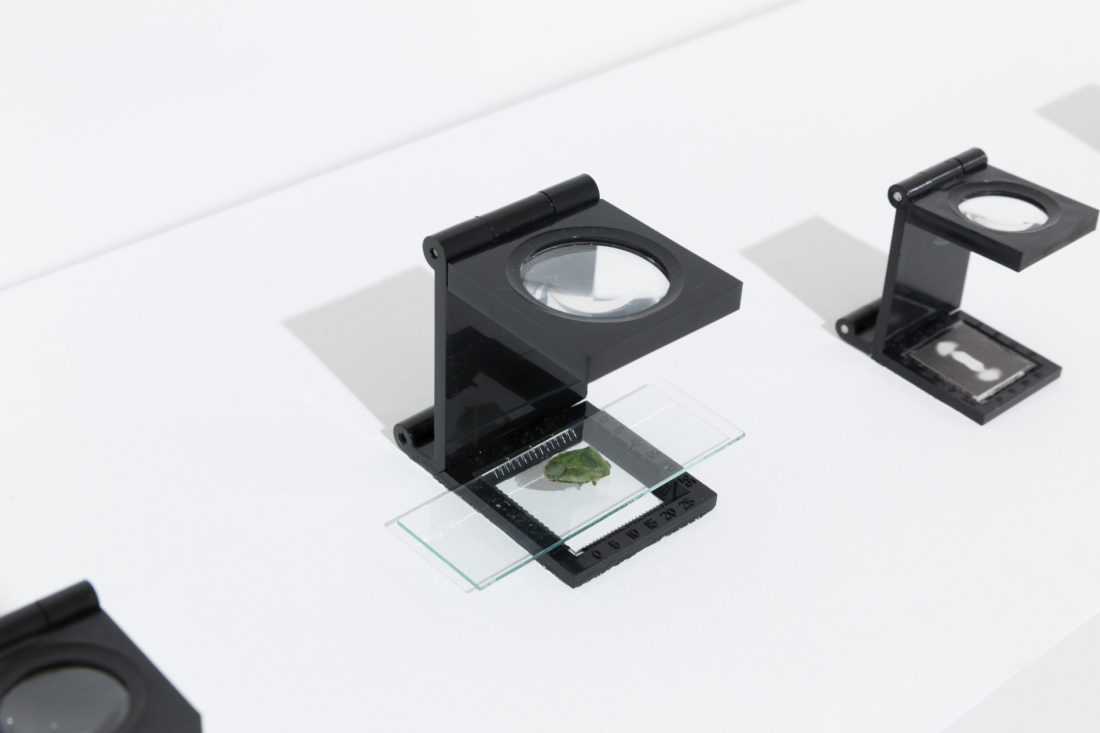

Max Pensky elaborates Benjamin’s metaphor, noting that constellations are at once a vestige of myths and tools of navigational science. In their duality, he argues constellations both retain and negate myth. It is in this sense, that the constellation is an apt concept for Carrillo’s installation. For she subjects the datum of Orozco’s life and person—his birthdate, his private correspondence, the contours of his hand—to the analytic systems of ancient divining practices that are simultaneously employed and refuted by modern forensic science. Her objects have the appearance of lab specimens, astronomical photographs, or archival documentation. And yet the person they attempt to bring into focus is nowhere to be found. Instead, each object represents a symbolic rendering of information about Orozco that Carrillo gleaned through in-depth readings of his astrological charts, his handwritten letters to his wife Margarita Valladares, or his grandson’s hands. (5)

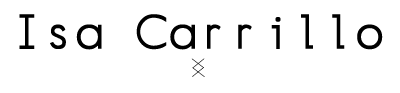

Thus, the concentration of gunpowder contained in the test tubes in Miscalculation (Cosmic Dust) approximates the proportion necessary to achieve the blast that destroyed the artist’s hand. But it also relates to the relationship between fire and earth signs in astrology, and the fact that these predominated on both Orozco’s birthday and the date of his accident. Likewise, the lunar eclipse in Hidden Messages recalls the fact that Orozco’s residency in Claremont coincided with one of these events. However, Carrillo also notes that Orozco’s moon was in Virgo, giving him a tendency to analyze and control rather than to follow his emotions.

Through this esoteric science, Carrillo creates what she calls an “invisible sculpture” not only of Orozco’s missing left hand, but also of the artist’s “sensibility and personality.” (6) The disparate objects in her installation collectively comprise a montage of fragments drawn from the detritus of modern life that retain their status as discreet phenomena while also pointing toward an ungraspable entity: the artist. The mythic idea of the artist that this object-constellation discloses is no more nor less manifest than the lunar eclipse rendered in a linocut or the stars envisioned through Stellarium (a free software program that generates images of the sky in the past from a specific location on earth) or the particle explosions captured in photographs from an old physics textbook. In each instance material techniques of representation index an immaterial reality that can be grasped but not fully possessed by the object. Like the man of fire who disintegrates in the act of self-creation, Carrillo’s Orozco is so much stardust “caught in the Devil’s bargain.”

1 Walter Benjamin, The Origins of German Tragic Drama, trans. by John Osborne (London: Verso, 1998), 34.

2 Joni Mitchell, Woodstock lyrics © Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC.

3 David Scott, “Orozco’s Prometheus: Summation, Transition, Innovation,” in José Clemente Orozco: Prometheus, ed. Marjorie Harth (Claremont, CA: Pomona College Museum of Art, 2002), 15.

4 Max Pensky, Melancholy Dialectics: Walter Benjamin and the Play of Mourning (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1993), 70.

5 Carillo worked with Graphologist Sandra Angelina Martínez Escobosa to analyze Orozco’s handwriting and Astrologer Alan Sierra to develop his Astrology Chart.

6 Personal correspondence between the artist and Curator Rebecca Mcgrew.